|

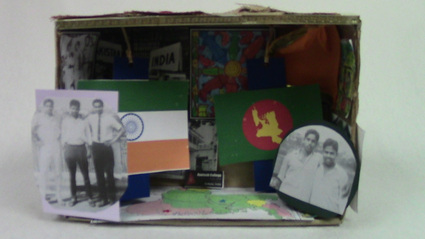

The Old Photographs on the front of the shadowbox are Sanjay Das as a young student in Kolkata. The Flag of India is to the left and the flag of Bangladesh (circa 1971) is to the right. The two flags also represent a new country emerging out of India. Pictures in the right interior symbolize tranquil village life before the West Pakistan invasion. Pictures in the left interior symbolize Kolkata changing as more and more refugees enter. The jhute or burlap on the top of the box represents the jhute mills that Sanjay Das’s family owned in Danga. Gold on the top and sides of the box represents the wealth that Hindu Bengali’s had and lost during the massacre. Fabric in the right interior represents a simple shawl that was used as covering and protection from the elements. Map on the interior bottom panel represents the partition of Bengal and the proximity between Kolkata and Dhaka. Newspaper articles on the outside panels of the box reports on the historical events that happened during the partition.

|

History is written by those who win the wars. It is told by the decisions of presidents, the heroism of the generals, and the evil of the enemy. It takes many decades for the stories of the survivors and the victims to surface. The plights of children who are trapped are the last ones to be heard.

When Sanjay Das was a fourteen year old boy he had to leave his family and his home in Danga, Bangladesh, formerly known as East Bengal. Overnight, Sanjay had to leave his school, his friends, the comforts of his home, and his childhood. After the British Raj had “Quit India,” they left it divided between India for the Hindus and Pakistan for Muslims. Common violence was erupting, and the horror was approaching the small village of Danga. There was an imminent war approaching, and the target was Hindu Bengali males.

In the city of Dhaka, the violence was horrific. Members of the Hindu community who were landowners, shopkeepers, and professors were robbed, and their families were then systematically slaughtered. The Hindu homes were painted with a yellow patch marked by the letter “H.” This was reminiscent of the way Jews were handled during the Holocaust. All of this was officially sanctioned, ordered, and implemented by the leaders from Islamabad. East Bengal was under Pakistani Islamist-led martial law.

Sanjay was the hope of his family. He was the right age to leave and migrate into neighboring Calcutta in India. Sanjay’s father and elder brothers had ancestral business in jute mills and cotton mills. They couldn’t leave their businesses and livelihood. Too many people, both Hindus and Muslims, depended on the operation of their mills. Sanjay had to pack a small bag of necessities for his trip which included his favorite books and a shawl to keep warm. He could pack only one set of clothes. In 1955, under the cover of the night, he had to walk to the port and get on a “steamer” boat, and then on a crowded train to Calcutta. Sanjay had to change his birth certificate and papers so that he could get into a boarding school. He knew that he had to study and get an education so that he could help his family survive. He had a sense of desperation to find any opportunities in Calcutta and save his family.

Sanjay was a very bright, focused, and attentive student. He never got less than 100% in any of his exams. He was known to be the boy who knew all the answers and was a hard worker. Sanjay had to fend for himself and persevere. He was admitted into the prestigious Asutosh College. Sanjay was able to help his younger brother, Pankaj, come to Calcutta to study. His father had died, and his two older brothers were still living in East Bengal. Slowly, Sanjay was able to bring his cousins and some family members to Calcutta. From age fourteen, he had to bear the enormous responsibility of being the provider and caretaker of his family.

As refugees flooded into Calcutta, news was heard about the execution areas and that people were killed by violent methods. Executions were held on a daily basis by the Pakistani militia. Human bones were scattered by the roadsides and blood stained clothing and human hair clung to the brush at these killing fields. The Saraswati River was turned RED by the blood of Hindu families. The people who remained were lost to their families and to the power of human hatred.

With faith and an incredible mental strength, Sanjay earned a degree in Metallurgical Engineering and started working in Durgapur Steel Mill. He had immersed himself in his new life and responsibilities. He lost many of his family members, many of whom were brutally murdered. During our interview, he spoke softly of an uncle who was buried alive and of another who was severed to separate pieces.

It was very difficult for Sanjay Das to speak to me about his survival. At first, he didn’t want to go into detail and wanted to only say things that are safe. He spoke about how lovely his village was and how the Muslims and Hindus families had lived in peace for hundreds of years. He spoke about brave Muslim friends who risked their lives and helped many Hindu families escape.

Sanjay Das and his remaining family eventually immigrated to the US in the 70's. He travels back and forth to India very often since first arriving to America. The last time he visited was in 1995, and he is going to leave soon to go back again. Today he is known by many as the happiest most positive person who always tries to look at the bright side of life, no matter how hard it gets.

When Sanjay Das was a fourteen year old boy he had to leave his family and his home in Danga, Bangladesh, formerly known as East Bengal. Overnight, Sanjay had to leave his school, his friends, the comforts of his home, and his childhood. After the British Raj had “Quit India,” they left it divided between India for the Hindus and Pakistan for Muslims. Common violence was erupting, and the horror was approaching the small village of Danga. There was an imminent war approaching, and the target was Hindu Bengali males.

In the city of Dhaka, the violence was horrific. Members of the Hindu community who were landowners, shopkeepers, and professors were robbed, and their families were then systematically slaughtered. The Hindu homes were painted with a yellow patch marked by the letter “H.” This was reminiscent of the way Jews were handled during the Holocaust. All of this was officially sanctioned, ordered, and implemented by the leaders from Islamabad. East Bengal was under Pakistani Islamist-led martial law.

Sanjay was the hope of his family. He was the right age to leave and migrate into neighboring Calcutta in India. Sanjay’s father and elder brothers had ancestral business in jute mills and cotton mills. They couldn’t leave their businesses and livelihood. Too many people, both Hindus and Muslims, depended on the operation of their mills. Sanjay had to pack a small bag of necessities for his trip which included his favorite books and a shawl to keep warm. He could pack only one set of clothes. In 1955, under the cover of the night, he had to walk to the port and get on a “steamer” boat, and then on a crowded train to Calcutta. Sanjay had to change his birth certificate and papers so that he could get into a boarding school. He knew that he had to study and get an education so that he could help his family survive. He had a sense of desperation to find any opportunities in Calcutta and save his family.

Sanjay was a very bright, focused, and attentive student. He never got less than 100% in any of his exams. He was known to be the boy who knew all the answers and was a hard worker. Sanjay had to fend for himself and persevere. He was admitted into the prestigious Asutosh College. Sanjay was able to help his younger brother, Pankaj, come to Calcutta to study. His father had died, and his two older brothers were still living in East Bengal. Slowly, Sanjay was able to bring his cousins and some family members to Calcutta. From age fourteen, he had to bear the enormous responsibility of being the provider and caretaker of his family.

As refugees flooded into Calcutta, news was heard about the execution areas and that people were killed by violent methods. Executions were held on a daily basis by the Pakistani militia. Human bones were scattered by the roadsides and blood stained clothing and human hair clung to the brush at these killing fields. The Saraswati River was turned RED by the blood of Hindu families. The people who remained were lost to their families and to the power of human hatred.

With faith and an incredible mental strength, Sanjay earned a degree in Metallurgical Engineering and started working in Durgapur Steel Mill. He had immersed himself in his new life and responsibilities. He lost many of his family members, many of whom were brutally murdered. During our interview, he spoke softly of an uncle who was buried alive and of another who was severed to separate pieces.

It was very difficult for Sanjay Das to speak to me about his survival. At first, he didn’t want to go into detail and wanted to only say things that are safe. He spoke about how lovely his village was and how the Muslims and Hindus families had lived in peace for hundreds of years. He spoke about brave Muslim friends who risked their lives and helped many Hindu families escape.

Sanjay Das and his remaining family eventually immigrated to the US in the 70's. He travels back and forth to India very often since first arriving to America. The last time he visited was in 1995, and he is going to leave soon to go back again. Today he is known by many as the happiest most positive person who always tries to look at the bright side of life, no matter how hard it gets.